Rohingya Refugee: Freedom to Fear

The persecution of the Rohingya — Myanmar's religious and ethnic minority community — dates back to 1948, which the country achieved independence from its British colonizers. Ever since repeated pleas for a promised autonomous state have been contemptuously rejected. On the contrary, inhuman barbarism heaped on the Rohingya — consistently classified as "illegal migrants" by successive Myanmar governments — has increased, with 2017 witnessing the high point of barbarism unleashed by the Myanmar military. Over 700,000 Rohingya then fled to neighboring Bangladesh.Interviewed Rohingya'sRohingya's from Myanmar who fled to Bangladesh, most of them said that "we fled from our country with fear to save our children and lives. We came here to find freedom. We feel we're safe here".

About the Exhibition :

This part of the project was exhibited at Four Freedoms Park Conservancy & United Photo Industries for "Capture your Freedom" at New York, an outdoor exhibition.

This exhibition presented four large-scale photographic cubes corresponding to each of the four freedoms -- freedom of speech & expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. The exhibition is the first of its kind held at the presidential memorial.

A panel of 6 esteemed photo editors and human rights advocates selected work by 30 photographers from around the world, which UPI produced in the form of four large-scale Photo Cubes on the picturesque Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park.

The participating artists are Ruthie Abel, Inbal Abergil, Patricia Ackerman, Kisha Bari, Susan Barnett, Sara Bennett, Paolo Bona, Valeria Bove, Vidhyaa C, Argus Paul Estabrook, Tom Finke, Carlos Gonzalez, Eliza Hatch, Louise Hon̩e, Ed Kashi, William King, Ryan Koopmans, Gioia Kuss, Jason Little, Liu Liu, Jorge Lopez Munoz, Calli McCaw, Marla Mossman, Fabian Muir, Cletus Nelson Nwadike, Hector Rene, Whitney Welshimer, Emma Williams, and Mohammad Zoyari.

Four Freedoms Park Conservancy and UPI assembled a panel of esteemed photo editors and human rights advocates, who offered their time, energy, and years of experience to this monumental outdoor exhibition to curate this public exhibition. The selection committee for Capture your Freedom was comprised of Penny Abeywardena, Commissioner, New York City Mayor'sMayor's Office For International Affairs; Yvette Alberdingk Thijm, Executive Director of Witness; Nathalie Applewhite, Managing Director of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting; Geoffrey Berliner, Executive Director of the Penumbra Foundation; Emma Raynes, Director of Programs at the Magnum Foundation; Maggie Soladay, Photography Editor at the Open Society Foundations in New York. Presented by Four Freedoms Park Conservancy in partnership with United Photo

However, a deep trust deficit in the powers that be in Myanmar is what reduces their aspirations to a mere pipe dream.

The memory of a lost country lives on. Beyond the exhilaration of breathing freedom, there remains a sense of mourning for their native land. For an exile, the joys of the present are quite perpetually dulled by the memories of the past

Rahima, 20, holds her three-month-old son Ahmed. “I fled to Bangladesh because of fear, now we are in Bangladesh , happy that I saved my child life. I was 8 month pregnant and suffering from fever while crossing the border. I also have three years old child, so it was very difficult to reach the border from our village in Myanmar. I had to rest frequently. After eight hours of horrible walking finally we crossed the border, paying the broker,” Rahima said.

Not only Rahima, many defenseless brave mothers faced different horrifying experience to save their live and their loved ones.

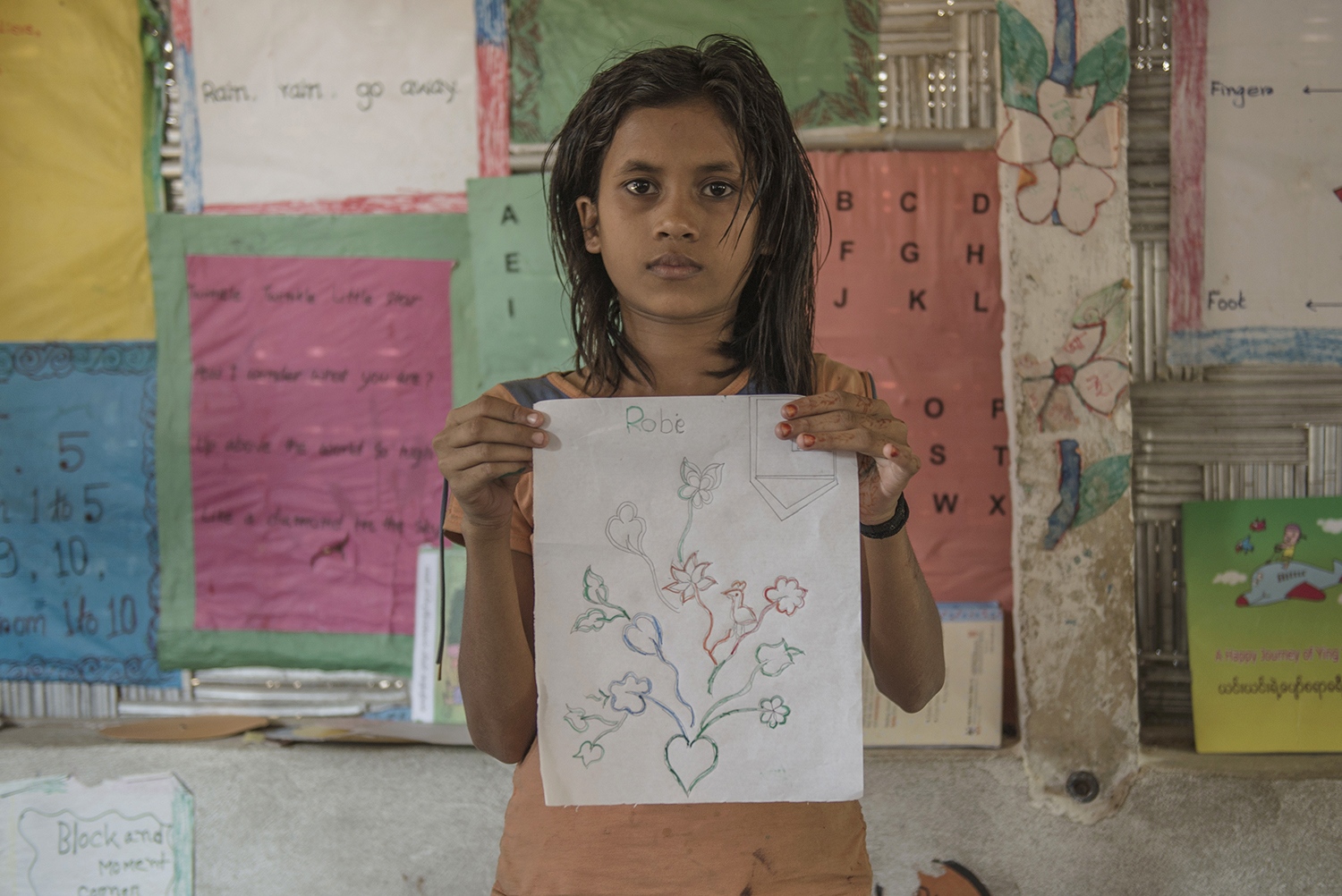

Trading in a host of goods and services keeps the Rohingya going, ranging from live chicken to haircuts to a host of labor jobs. Running their small businesses has resulted in forging new friendships, learning art, sending their children to school with the support of NGOs, even finding life partners, as was the case with Abdul.

Adbul, who does haircuts for living in a refugee camp, was part of an earlier 1977 exodus of over 200,000 Rohingya after the brutal army-ordered purge that year.

Abdul says the new-found freedom has come at a price. He revealed in an interview given to me that his people had been forced to abandon their loved ones besides everything they owned in the Rakhine region that was once their home.

Many are still traumatized by what they have experienced — most have no idea of the future that awaits them, Abdul adds, as he waits for his next customer.

Abdul is thankful that they experience safety and intellectual freedom, albeit weighed down by emotional distress that displacement brings. He reveals that the Rohingya refugees pine for a return to normal lives in their homeland, but which in the same breath, he adds, remains a pipe dream.

Work for Cash

Rubida Alam and her neighbors at work, for this work cash income, paid immediately to meet their food and basic requirements which was provided ACF and Mukti Cox Bazaar, BangladeshWe want rights and freedom

We want to go back to Myanmar, we want to live in peace and have citizenship rights and freedom before I die sadly”, said Rahman.

In Myanmar, the Rohingya have no human rights, discriminatory laws and practices which have effectively denied citizenship to Rohingya on the basis of their ethnicity.

The memories though of a lost country live on. Beyond the exhilaration of breathing freedom, there remains a sense of mourning for their native land. For one exiled, the joys of the present are dulled by the reminiscences of the past.